Home | Card Index | | | |

Home | Card Index | | | | |

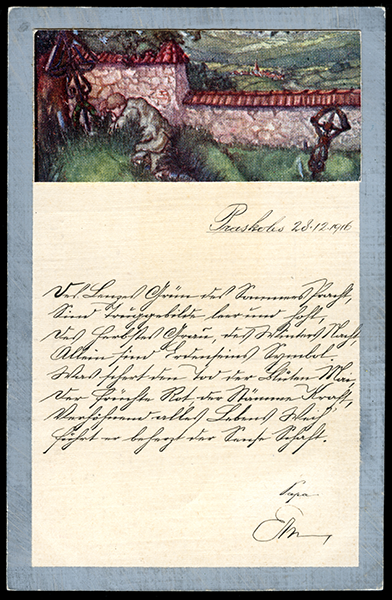

Eman Robitschek to Frida Robitschek - December 28, 1916Transcription and translation by Werner Sepper. |

|

Des Lenzes Grün, Des Sommers Pracht, The green of spring, the summer's splendor, Note: |

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

Note: |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Die Geschichte ist ein Sym- |

History is a symbol *(Klio) Clio is the Muse of History. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The chandelier is crowned by the Hapsburg double eagle, but there are no candles in the candle holders. The light of the Holy Roman Empire, and with it the catholic church, has been extinguished and repressed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

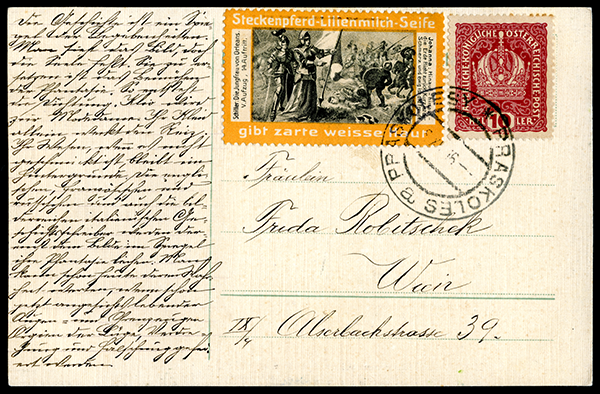

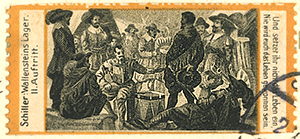

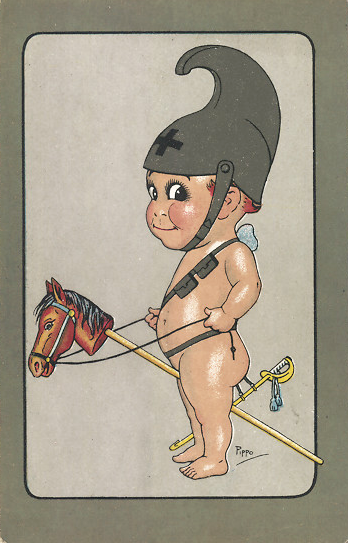

Eman uses the advertising label for Steckenpferd Lilienmilch Soap, seen above, to reveal another of Clio's bitter truths - history's true nature. The cut label at the left, which he uses on another card, shows that he is deliberately leaving the advertising label in tact. |

|

We know that he is using the advertising label knowingly and deliberately because on another card, dated 26 days earlier, he used another Steckenpferd Lillenmilche label from the same commemorative series, but carefully cuts off the brand and tagline because they are not pertinent to the subject of that card. The tag line for this soap is "For Soft White Skin." Typically, advertising labels for Lilienmilch Soap depict beautiful women and babies, but this one depicts a scene from Friedrich Schiller's epic poem about Joan of Arc, Die Jungfrau von Orleans, and even provides the specific verse being quoted (portion on the label in italics): |

|

|

"You see the rainbow in the air? |

|

|

In fact, the picture on the label does not show a rainbow, the parting of the heavens, or Johanna's ascension; it portrays men killing one another in war. Yes, Eman is saying, bloody, brutal war is how men choose to cleanse society to reveal the soft white "skin" beneath.

|

||

|

Steckenpferd is a trademark of Bergmann & Co. Under this trademark, three soap brands were marketed: Lilienmilch, Buttermilch, and Teerschwefel; also a line of cosmetics called Dada, which is a French idiom meaning Steckenpferd or "Hobbyhorse." Up through WWI, hobbyhorses were popular and culturally important toys for boys. With them, they could dream of being cavalry officers. In this way, the Steckenpferd trademark is, itself, connected with war. |

|

|

||

|

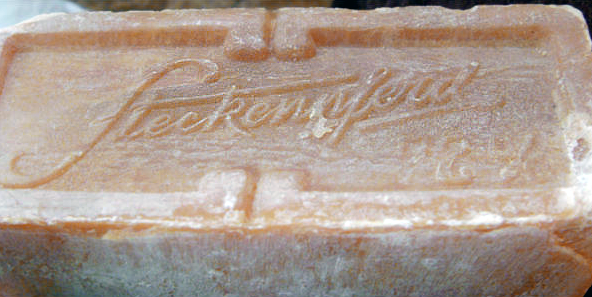

Steckenpferd has another close connection with the sudsier aspects of war. Bergmann's Teerschwefelseife, which means "Pine Tar Sulfur Soap," pictured above, was used to wash animals, primarily horses and mules. The biggest customer for this product was the military. Bergmann & Co. was founded in 1885. It seems likely that Steckenpferd was a nod to the early importance of it's pine tar soap for horses. |

Last updated 3/11/2014 |

|

|

|

©2013-2014 by Charles M. Nelson All rights reserved. |