Course Home | Setting | Nile Hydrology | Predynastic Development | Dynastic Egypt |

Course Home | Setting | Nile Hydrology | Predynastic Development | Dynastic Egypt | |

The Nile in Geographic Context |

||

| LAST UPDATE: 10-25-2012 | ||

|

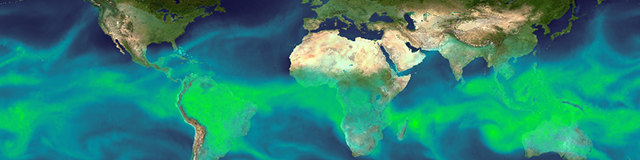

Although at its height, the Egyptian Kingdom extended southward to the confluence of the Blue Nile and the White Nile (left), its heartland always consisted of the entrenched floodplain, delta and Fayum Basin, highlighted above in green. It is technological, economic, social and religious innovations in this region that allowed the kingdom to grow and flourish for three millennia. |

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

This is the first cataract at Aswan. We are just south of the head of the cataract looking north where the Nile is suddenly blocked by a series of resistant rocks, causing the river to divide into a number of shallow reaches. A series of these cataracts prevent the river from deeply incising its valley and promote the development of the agriculturally fertile floodplain necessary for the development of ancient civilization in the Nile Valley. |

||

|

The narrow channels of the First Cataract, at Aswan, can be navigated by small vessels with with only a little draft, but large vessels can't easily pass even at high water. A number of the other cataracts are even more difficult to navigate. |

||

|

The hatched region that contains many units of very hard rock, such as granite. Where thee units run beneath the Nile River, they form "cataracts" that make erosion very difficult and cause sediment to be retained on the upstream side. They also cause the river to meander, which widens the valley, creating and sustaining a broader floodplain. Without such formations, the Nile would incise a deeper, narrower valley with less agricultural potential. |

||

|

The Nile delivers enormous amounts of sediment to the sea, forming a vast delta, most of which is actually underwater. The area not underwater is about 25,000 square km. (about 9,600 square mi. or the size of Vermont), most of which is in continuous agricultural production. |

||

|

Early in the wet season where the Ruvubu enters the Kagera River in Rwanda, in the headwaters of the Nile. |

||

|

The Masai Mara just east of Lake Victoria. |

||

|

Gorge near Murchison Falls below Lake Victoria. |

||

|

Satellite view of Lake Albert. |

||

|

Savana & woodlands along the Albert Nile. |

||

|

Map of the Sudd. |

||

|

Typical area in the lower Sudd. |

||

|

Households on small floating islands in the Sudd. |

||

|

Village along the open Nile in the Sudd. |

||

|

Arid steppe in Butana, Sudan. |

||

|

Ethiopian Highlands - source of the Blue Nile. |

||

|

The Blue Nile in flood ... thus, not so blue. |

||

|

The Nile floodplain from on high. |

||

|

The Nile floodplain from on high. |

||

|

The Nile floodplain on the ground. |

||

|

The Fayoum Depression and Nile Delta by night. |

||

|

On the ground in the Fayoum. |

||

|

Typical scene in the Nile Delta. |

||

|

©2012 by Charles M. Nelson All rights reserved. |